KSL INVESTIGATES

Location data cracks open police cases, but critics say there’s a cost to privacy

Aug 18, 2022, 10:19 PM | Updated: Nov 21, 2022, 11:35 pm

SALT LAKE CITY – The drive through Interstate 15 in Utah’s Juab County turned chaotic and violent in November when a shooter fired at other cars while passing them, grazing one woman and striking a man in the shoulder.

But tracking down a suspect wasn’t easy. No one on the road got a good look at the aggressor.

Police obtained smartphone location data from several who passed through at the time, narrowing the field to four people, then eventually to one, according to courtroom testimony.

Officers arrested a Goshen, Utah, man, Adam Lloyd Gheen nearly six months after the shooting. He was ordered to stand trial last week on five counts of attempted murder.

The investigative technique is increasingly common. When they don’t know exactly who they’re looking for, police in the Beehive State and across the country are turning to the cloud to identify perpetrators.

With warrants for location data – often called geofence or reverse location warrants – police can draw a digital border around an area and collect information from Google about phones there at a given time.

They don’t receive any identifying information the first time around, but they can return with another warrant to find out who certain devices belong to.

Without this technique, some law enforcers say there are crimes that will never be solved. But privacy advocates say the practice is unconstitutional, amounting to an unlawful search.

The “Wild West”

Debate over geofence warrants is playing out in courtrooms and statehouses across the country, spurred in part by reports of a wrongful arrest in Arizona.

Earlier this year, a federal judge in Virginia ruled police violated the rights of innocent people by sweeping up their data in a robbery investigation. And a pending bill in New York, if it passes, would be first in the nation to ban the use of geofence warrants.

Utah already requires police to get approval from a judge to legally obtain the location data. So does Google. Now, for the second year in a row, state lawmakers are exploring greater limits on how and when investigators can access the information.

“Right now, because it isn’t a defined area of law, it’s sort of the Wild, Wild West,” Utah state Rep. Ryan Wilcox, an Ogden Republican said. He sponsored a proposal last year that won approval in the House but didn’t get a vote in the Senate. An interim legislative law enforcement committee – that Wilcox chairs – voted unanimously to revive the bill, but it’s still hammering out the details of a new version.

Throughout Utah, law enforcers are asking for and obtaining reverse location warrants in cases ranging from high-profile homicides to credit card theft and shoplifting.

In the case of the freeway shooter, data from Google led police to Gheen, but they’re still holding onto information from three other user accounts swept up in the search, according to State Bureau of Investigation agent Jeffery Kinghorn.

“The other three are currently under investigation,” Kinghorn testified at an Aug. 10 preliminary hearing.

An “unconstitutional abuse”

Leslie Corbly with the libertarian-leaning Libertas Institute says this approach to policing can violate the Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable search and seizure.

Leslie Corbly, privacy policy analyst with the libertarian-leaning Libertas Institute, says it’s time for Utah lawmakers to place limits on the use of geofence warrants.

In order to search your home, police have to provide evidence linking you to a crime, Corbly noted. But the virtual searches are different.

If they already had those specifics on where you were – or even who you are – they wouldn’t need to seek out the data in the first place, Corbly said. The very point of geofence warrants is to fill in the blanks.

“You can’t just search someone because they were close to a crime,” Corbly added. “So that’s where you get these concerns of, ‘Are these warrants not sufficient to meet constitutional requirements?’ ”

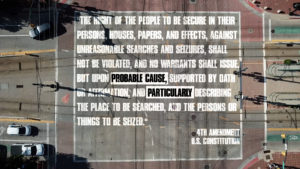

The Fourth Amendment states that government must “particularly” describe the “persons or things to be seized.” And it must provide enough evidence to meet the standard of probable cause.

Libertas and other privacy advocates contend geofence warrants don’t do either. And they say the data collected for marketing purposes isn’t always precise, so an error could implicate you in a crime you had nothing to do with.

In Gheen’s case, prosecutors argued there’s other evidence tying Gheen to the crime. But his defense attorney Staci Visser told the KSL Investigators the potential for skewed geofence returns makes “reliance on this data to support an arrest warrant or potentially a conviction very troublesome.”

In an August report calling the warrants an “unconstitutional abuse of technology,” Libertas analyzed geofence warrants filed in Utah’s court system in recent years, finding several tied to crimes like kidnapping, aggravated robbery and homicide. But others sought dumps of location data for lower-level offenses, like burglaries. One granted Layton police approval to track down whoever stole a credit card and used it to buy about $60 in gas before stopping at Del Taco and Taco Bell in Ogden.

“Checks all along the way”

If a judge signs off on this type of warrant, deputy Utah County Attorney Ryan McBride noted the first batch of information keeps smartphone users anonymous to investigators.

Deputy Utah County Attorney Ryan McBride emphasizes that in order to obtain geolocation data, law enforcers first must get approval from a judge.

Once they want to unmask – or get identifying data about people – they need another warrant from a judge weighing the strength of the evidence in hand against people’s privacy rights.

“I think it’s important for people to realize there are checks all along the way,” McBride said.

The data is especially helpful to investigators in two situations, McBride said. The first is when a crime takes place in rural areas where few people tend to go. The second is when there’s a string of crimes at multiple places, like similar bank robberies across a city.

The location data has played a role only in the most serious cases McBride has worked on – less than a dozen in total – he said.

For example, it helped solve the double murder of Eureka,Utah teenagers Breezy Otteson and Riley Powell in Utah’s west desert, the prosecutor said. A lack of devices in the area helped rule out the possibility that anyone other than Jerrod Baum and his girlfriend were present at the time of the teenagers’ deaths. A jury found Baum guilty of two counts of aggravated murder in April.

“Without it, there certainly will be crimes that are not solved,” McBride said.

“Not an easy line to distinguish”

Wilcox agrees, but he said Utah needs to take more steps to protect “the innocent public.”

“It’s not an easy line to distinguish,” he said.

There’s no draft of the new bill yet, but it will require law enforcers to report to lawmakers data on the location information they use, Wilcox said. Wilcox said his unsuccessful 2021 measure – prohibiting the release of a person’s name, address, phone number, or email in response to a broad geolocation inquiry — is a starting point. The bill would stipulate that if police want that information, they need to demonstrate probable cause the phone user was involved in a crime.

The Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice Interim Committee is expected to debate the topic again in September.

Corbly is concerned about other large databases tracking the habits of smartphone users – and the ways authorities may want to use them.

“What’s important to understand,” she said, “is that this is the tip of the iceberg as far as what a reverse warrant can do.”

This story from the KSL Investigators is one in a series exploring the state of data privacy and policing in Utah. Have you experienced something you think just isn’t right? The KSL Investigators want to help. Submit your tip at investigates@ksl.com or 385-707-6153 so we can get working for you.